Deviation From Ideal Gas Behavior

Table of Content |

|

|

A gas which obeys the gas laws and the gas equation PV = nRT strictly at all temperatures and pressures is said to be an ideal gas.The molecules of ideal gases are assumed to be volume less points with no attractive forces between one another. But no real gas strictly obeys the gas equation at all temperatures and pressures. Deviations from ideal behaviour are observed particularly at high pressures or low temperatures.

A gas which obeys the gas laws and the gas equation PV = nRT strictly at all temperatures and pressures is said to be an ideal gas.The molecules of ideal gases are assumed to be volume less points with no attractive forces between one another. But no real gas strictly obeys the gas equation at all temperatures and pressures. Deviations from ideal behaviour are observed particularly at high pressures or low temperatures.The deviation from ideal behaviour is expressed by introducing a factor Z known as compressibility factor in the ideal gas equation. Z may be expressed as Z = PV / nRT

|

Thus in case of real gases Z can be < 1 or > 1

Thus in case of real gases Z can be < 1 or > 1

-

When Z < 1, it is a negative deviation. It shows that the gas is more compressible than expected from ideal behaviour.

-

When Z > 1, it is a positive deviation. It shows that the gas is less compressible than expected from ideal behaviour.

Causes of Deviation from Ideal Behaviour

The causes of deviations from ideal behaviour may be due to the following two assumptions of kinetic theory of gases.

-

The volume occupied by gas molecules is negligibly small as compared to the volume occupied by the gas.

-

The forces of attraction between gas molecules are negligible.

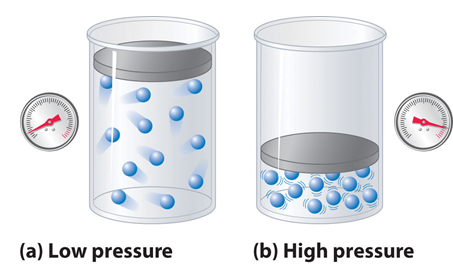

The first assumption is valid only at low pressures and high temperature, when the volume occupied by the gas molecules is negligible as compared to the total volume of the gas. But at low temperature or at high pressure, the molecules being in compressible the volumes of molecules are no more negligible as compared to the total volume of the gas.

The second assumption is not valid when the pressure is high and temperature is low. But at high pressure or low temperature when the total volume of gas is small, the forces of attraction become appreciable and cannot be ignored.

Van der Waals’ Equation of State for a Real Gas

This equation can be derived by considering a real gas and 'converting ' it to an ideal gas.

Volume Correction

Hence, Ideal volume

Vi = V – nb …..........(i)

n = Number of moles of real gas

V = Volume of the gas

b = A constant whose value depends upon the nature of the gas

|

The Van der Waals constant b (the excluded volume) is actually 4 times the volume of a single molecule. |

b = 4 × volume of a single molecule = 4 × 6.023 × 1023 ×(4/3) r3, where r is the radius of a molecule.

r3, where r is the radius of a molecule.

Pressure Correction

Let us assume that the real gas exerts a pressure P. The molecules that exert the force on the container will get attracted by molecules of the immediate layer which are assumed not to be exerting pressure.

It can be seen that the pressure the real gas exerts would be less than the pressure an ideal gas would have exerted. The real gas experiences attractions by its molecules in the reverse direction. Therefore if a real gas exerts a pressure P, then an ideal gas would exert a pressure equal to P + p (p is the pressure lost by the gas molecules due to attractions).

This small pressure p would be directly proportional to the extent of attraction between the molecules which are hitting the container wall and the molecules which are attracting these.

Therefore p ∝ n/v (concentration of molecules which are hitting the container's wall)

P ∝ n/v (concentration of molecules which are attracting these molecules)  p ∝ n2/v2

p ∝ n2/v2

P = an2/v2 where a is the constant of proportionality which depends on the nature of gas.

A higher value of 'a' reflects the increased attraction between gas molecules.

Hence ideal pressure

Pi = (P + an2 / V2) …...........(ii)

Here,

n = Number of moles of real gas

V = Volume of the gas

a = A constant whose value depends upon the nature of the gas

Substituting the values of ideal volume and ideal pressure in ideal gas equation i.e. pV=nRT, the modified equation is obtained as

|

Different forms of Van der Waal’s equation

-

At Low Pressures

‘V’ is large and ‘b’ is negligible in comparison with V.

‘V’ is large and ‘b’ is negligible in comparison with V.

The Vander Waals equation reduces to:

(P + a / V2) V = RT;

PV + a/ V = RT

PV = RT – a/V or PV < RT

This accounts for the dip in PV vs P isotherm at low pressures.

-

At Fairly High Pressures

a/V2 may be neglected in comparison with P.

a/V2 may be neglected in comparison with P.

The Vander Waals equation becomes

P (V – b) = RT

PV – Pb = RT

This accounts for the rising parts of the PV vs P isotherm at high pressures.

-

At Very Low Pressures

V becomes so large that both b and a/V2 become negligible and the Vander Waals equation reduces to PV = RT. This shows why gases approach ideal behaviour at very low pressures.

-

Hydrogen and Helium

These are two lightest gases known. Their molecules have very small masses. The attractive forces between such molecules will be extensively small. So a/V2 is negligible even at ordinary temperatures.

Thus PV > RT. Thus Vander Waals equation explains quantitatively the observed behaviour of real gases and so is an improvement over the ideal gas equation. Vander Waals equation accounts for the behaviour of real gases.

At low pressures, the gas equation can be written as,

(P + a/v2m) (Vm) = RT

or

Z = Vm / RT = 1 – a/VmRT

Where Z is known as compressibility factor. Its value at low pressure is less than 1 and it decreases with increase of P. For a given value of Vm, Z has more value at higher temperature.

At high pressures, the gas equation can be written as

P (Vm – b) = RT

Z = PVm / RT = 1 + Pb / RT

Here, the compressibility factor increases with increase of pressure at constant temperature and it decreases with increase of temperature at constant pressure. For the gases H2 and He, the above behaviour is observed even at low pressures, since for these gases, the value of ‘a’ is extremely small.

Some Other Important Definitions

-

Relative Humidity (RH)

At a given temperature it is given by equation

RH = (partial pressure of water in air) / (vapour pressure of water )

-

Boyle’s Temperature (Tb)

Temperature at which real gas obeys the gas laws over a wide range of pressure is called Boyle’s Temperature. Gases which are easily liquefied have a high Boyle’s temperature [Tb(O2)] = 46 K] whereas the gases which are difficult to liquefy have a low Boyle’s temperature [Tb(He) = 26K].

Boyle’s temperature(Tb) = a / Rb = 1/2 T1

where Ti is called Inversion Temperature and a, b are called van der Waals constant.

It (Tc) is the maximum temperature at which a gas can be liquefied i.e. the temperature above which a gas can’t exist as liquid.

T = 8a / 27Rb

-

Critical Pressure (Pc)

It is the minimum pressure required to cause liquefaction at Tc

Pc = a/27b2

-

Critical Volume

It is the volume occupied by one mol of a gas at Tc and Pc

Vc = 3b

Molar Heat Capacity of Ideal Gases

Specific heat c, of a substance is defined as the amount of heat required to raise the temperature of is defined as the amount of heat required to raise the temperature of 1 g of substance through 10C, the unit of specific heat is calorie g-1 K-1. (1 cal is defined as the amount of heat required to raise the temperature of 1 g of water through 10C)

Molar heat capacity C, is defined as the amount of heat required to raise the temperature of 1 mole of a gas through 10C. Thus,

Molar heat capacity = Sp. Heat molecular wt. Of the gas

For gases there are two values of molar heats, i.e., molar heat at constant pressure and molar heat at constant molar heat at constant volume respectively denoted by Cp and Cv. Cp is greater than Cv and Cp-R = 2 cal mol-1 K-1

From the ratio of Cp and Cv, we get the idea of atomicity of gas.

For monatomic gas Cp = 5 cal and Cv =3 cal

∴ (γ = 5/3 = 1.67 (γ is poisson's ratio = Cp / Cv)

For diatomic gas Cp = 7 cal and Cv = 5 cal

γ = 7/5 = 1.40

For polyatomic gas Cp = 8 cal and Cv= cal

γ = 8/6 = 1.33

also Cp = Cpm,

where, Cp and Cv are specific heat and m, is molecular weight.

Example 3: |

QuestionCalculate Vander Waals constants for ethylene TC = 282.8 k; PC = 50 atm Solution: b = 1/8 RTc / Pc = 1/8 × 0.082 × 282.8 / 50 = 0.057 litres/mole a = 27 / 64 R2 × T2C / Pc = 27/64 × (0.082)2 × (282.8)2 × 1/50 = 4.47 lit2 atm mole–2 |

Question 1: When Z < 1 , it showns

a. a negative deviation

b. a positive deviation.

c. that the gas is showing ideal behaviour

d. that the gas is less compressible than expected from ideal behaviour

Question 2: A real gas behaves ideally at

a. high temperature and low pressure

b. high temperature and high pressure

c. low temperature and high pressure

d. low temperature and low pressure

Question 3: Which of the following equations represents the correct form of Vandear waal’s equation at very low pressure?

a. PV = RT – a/V

b. pV = nRT

c. P (Vm – b) = RT

d. P (V – b) = RT

Question 4: The maximum temperature at which a gas can be liquefied is called

a.boiling point.

b. melting point

c. Boyle’s temperature

|

Q.1 |

Q.2 |

Q.3 |

Q.4 |

|

a |

a |

b |

d |

Related Resources

-

Click here to go through JEE Chemistry Syllabus

-

Look here for Reference books for IIT JEE

-

You can also refe to the Ideal Gas Law & Dalton’s Law of Partial Pressure

To read more, Buy study materials of States of Matter comprising study notes, revision notes, video lectures, previous year solved questions etc. Also browse for more study materials on Chemistry here.

View courses by askIITians

Design classes One-on-One in your own way with Top IITians/Medical Professionals

Click Here Know More

Complete Self Study Package designed by Industry Leading Experts

Click Here Know More

Live 1-1 coding classes to unleash the Creator in your Child

Click Here Know More

a Complete All-in-One Study package Fully Loaded inside a Tablet!

Click Here Know MoreAsk a Doubt

Get your questions answered by the expert for free