Monotonicity

Table of Content |

Monotonicity is an important part of application of derivatives. The monotonicity of a function gives an idea about the behaviour of the function. A function which is either completely non-increasing or completely non-decreasing is said to be monotonic.

A function is said to be monotonic if it is either increasing or decreasing in its entire domain.

eg : f(x) = 2x + 3 is an increasing function while f(x) = -x3 is a decreasing function.

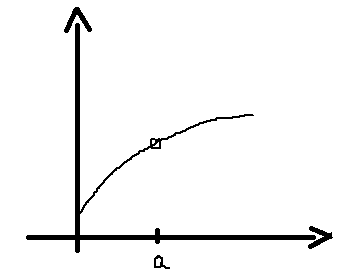

Increasing Function:

If x1 < x2 and f(x1) < f(x2) then the function is called increasing function or strictly increasing function.

If x1 < x2 but f(x1) > f(x2) in the entire domain, then the function is said to be a decreasing function or strictly decreasing function.

Functions which are increasing as well as decreasing in their domain are said to be non-monotonic functions.

f(x) = sin x is non-monotonic but is increasing in the interval [0, π/2].

We can talk of the concept of monotonicity either at a point or in an interval:

A function is said to be monotonically increasing at x = a if f(x) satisfies:

f(a + h) > f(a) and

f(a - h) < f(a) , for a small positive h.

A function is said to be monotonically decreasing at x = a if f(x) satisfies:

f(a + h) < f(a) and

f(a – h) > f(a) , for a small positive h.

Note: We can talk of monotonicity of f(x) at x = a only if x = a lies in the domain of f(x) without any restriction of continuity or differentiability of f(x) at x = a.

For an increasing function in some interval

if Δx > 0 ⇔ Δy > 0 or Δx < 0 ⇔ Δy < 0, then f is said to be monotonic (strictly) increasing in that interval.

In other words, we can say that if dy/dx > 0 in some interval then y is said to be an increasing function in that interval. Also, if the function f(x) is increasing in some interval, then dy/dx > 0 in that interval.

Similarly, if dy/dx < 0 in some inetrval then y is said to be an decreasing function in that interval. Also, if the function f(x) is decreasing in some interval, then dy/dx < 0 in that interval.

Example: Prove that f(x) = x – sin x is an increasing function.

Solution: f(x) = x – sin x

So, f’(x) = 1- cos x

Now, f’(x) > 0 everywhere except at x = 0, ±2π, ±4π etc. but since all of these points are discrete and do not form an interval, hence, we can conclude that f(x) is monotonically increasing for x ∈ R.

A function f(x) is said to be non-decreasing in the domain, if for every x1, x2 ∈ D, x1 > x2 and f(x1) ≥ f(x2). In other words, it means that the value of the function f(x) would never decrease with an increase in the value of x.

Similarly, f(x) is said to be non-increasing in a domain if for every x1, x2 ∈ D*, x1 > x2 and f(x1) ≤ f(x2). In other words, it means that the value of the function f(x) would never increase with an increase in the value of x.

If a function is monotonic at x = a it cannot have extremum point at x = a and conversely i.e. a point on the curve cannot simultaneously be an extremum as well as monotonic point.

If f is increasing then nothing definite can be said about the function f’(x) as to whether it is increasing or decreasing.

Case 1: If a function y = f(x) is strictly increasing in the closed interval [a,b] then f(a) is the least value and f(b) is the greatest value.

Case 2: If f(x) is decreasing in [a,b] then f(b) is the least and f(a) is the greatest value of f(x) in [a,b].

Case 3: If (x) is non-monotonic in [a,b] and is continuous then the greatest and least value of f(x) in [a,b] are those where f(x) = 0 or f’(x) does not exist or at the extreme values.

Let us now discuss some examples based on this concept:

Example 1: Find the set of values of x for which ln(1 + x) > x/(1 + x)

Solution: The given function is f(x) = ln(1 + x) – x/(1 + x)

= ln(1 + x) + 1/(1 + x) – 1

Domain: x > -1

f’(x) = 1/(1 +x) – 1/(1 + x)2 = x/(1 + x)2

f’(x) ≥ 0 ∀ x ≥ 0.

This means that f(x) is increasing

and f’(x) ≤ 0 ∀ x ≤ 0.

This means that f(x) is decreasing.

and f’(0) = 0

Therefore, f(x) > f(0) ∀ x ∈ Df – {0}

Therefore, f(x) > 0 ∀ x ∈ (-1, 0) ∪ (0,∞).

Example 2: Show that the equation x5 – 3x – 1 = 0 has a unique root in [1,2].

Solution: Consider the function x5 - 3x – 1 = 0, x ∈ [1,2].

and f’(x) = 5x4 – 3 > 0∀ x ∈ [1,2].

So, f(x) is strictly increasing in [1,2].

Also, we have f(1) = 1 - 3 - 1 = -3.

f(2) = 32 – 6 – 1 = 25

From the shape of the curve, we can see that the curve y = f(x) will cut the x-axis exactly once in [1,2].

So, f(x) will vanish exactly once in [1,2].

Example 3: Prove that x/(1 + x) < ln(1 + x) < x ∀ x > 0.

Solution: Consider the function f(x) = ln(1 + x) - x/(1 + x), x > 0.

then, f‘(x) = x/(1 + x) – x/(1 + x)2 = x/(1 + x)2 > 0 ∀ x > 0

So, f(x) is strictly increasing in (0, ∞)

So, f(x) > f(0+) = 0

i.e. ln(1 + x) > x/(1 + x) which proves the first inequality.

now, consider the function g(x) = x – ln(1 + x), x > 0

then g’(x) = 1 – 1/(1+x)

= x/(1 + x) > 0 ∀ x > 0

So, g(x) is strictly increasing in (0, ∞).

This means g(x) > g(0+) = 0

So, x > ln(1+x) which proves the second part of inequality.

Example 4: Find the intervals in which the function f (x) = 2x2 – ln |x| is

(i) decreasing (ii) increasing

Solution: f (x) = 2x2 – ln |x|

f'(x) = 4x – 1/|x|.|x|/x ⇒ f' (x) = 4x2–1/x

for increasing function f (x), f' (x) > 0

⇒ 4x2–1/x > 0

⇒ x ∈ (–1/2, 0) U (1/2, ∞)

for decreasing function f (x), f' (x) < 0

⇒ 4x2 – 1/x < 0

⇒ x ∈ (∞, –1/2) U (0, 1/2)